A UFO 50 Diaries pitstop

Some thoughts on the most generous game ever made

Since we’re at the halfway point of this series, I wanted to take a moment to put some more general thoughts to paper on how I feel about this game collection so far. Its highs, its lows, and how I feel in light of not really knowing if which decisions are intentional, and which are the product of developmental constraints.

UFO 50 has undoubtedly been a brilliant experience, and I think I’ve really gained a lot from pursuing this ‘one game per week’ model. My general rule has been, where possible, to give each title at least an hour of my time, including the ones I normally would have bounced off of in the first five minutes, and I’ve seen on multiple occasions the benefit of this kind of commitment.

The thing about a collection of games like this, in which there is no barrier to starting any title at any time, is that it has been designed not to be played as much as it has to be played. You pick the experiences you really gel with, and don’t worry too much about the ones you don’t. Some genres will inevitably appeal more than others. Some specific games will be the one you come back to time and time again.

I sank ten hours into Block Koala alone, playing not only to completion but to the cherry condition also, simply because I really enjoyed the Sokoban element of that game. Consequently titles like Bushido Ball and Ninpek are likely experiences I won’t return to any time soon, because I just didn’t vibe with them.

Rather paradoxically though, as much as picking the things you want to engage with is very much the name of the game, that’s not the only way to play. As I discussed in my video on the subject last year, I do still champion this idea of giving each title the time it deserves, and the reason for this is that its not always going to be apparent which games ignite that fire within you right from the get go.

I needed several attempts at Mooncat to realize that it might be the best platformer I’ve ever played, to use but one example. I think its one of the true triumphs of the collection that I find this happening again and again. Where games didn’t quite tickle my fancy, I had a seemingly endless supply of things to write about nonetheless.

Great content fodder, this, huh?

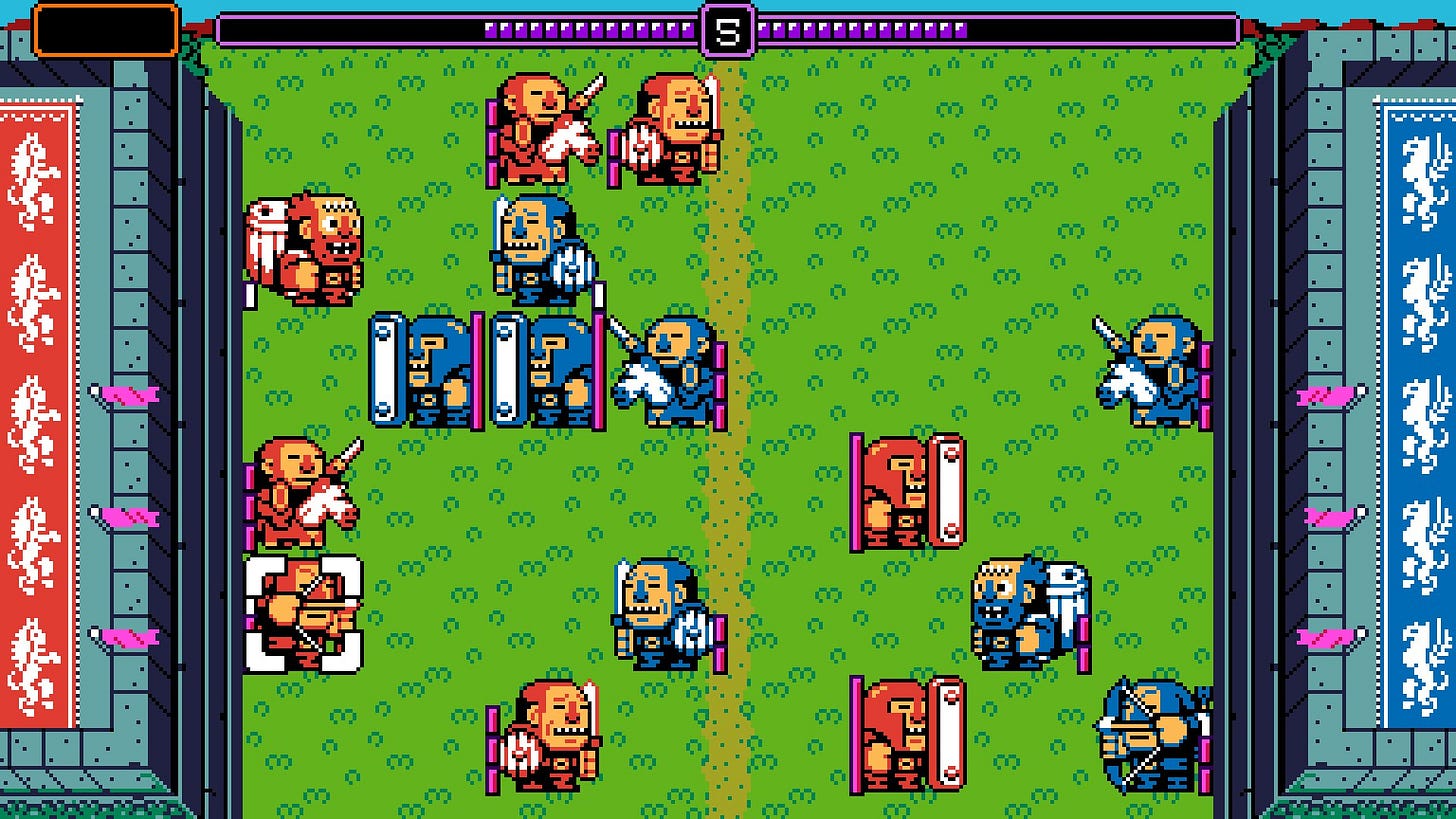

For those who really want to get into the weeds of the game, there is something there tying all of these things together. A historical context, a narrative context and a mechanical context of evolution, of how games change over time, what inspirations they take from the world and from each other.

Not so much a duality, as a triad of concepts, or even a quadrilateral idea space, UFO 50 has so much going on beyond what’s present in each specific game that I could easily see this diary series running for another year, or even two.

It’s not just that the little blurbs attached to each game, alongside subtle clues in the credits of each title, build up this narrative of the relationship that this fictional developer has with its games and with its own staff. There is also a mechanical narrative being played, an evolution of ideas across these games. You see the spirit of early titles in later ones, motif’s reused and remixed into concepts entirely new. It’s a story without a story, and that’s really cool.

Purely on the mechanical side, what’s particularly brilliant here, and why I think this project could only have been made by the team that built it, is how much complexity is drawn from just two buttons. That constraint must have seemed maddening during development. Ideas having to be redrawn or even abandoned on the basis of simply not fitting within this restrictive framework.

What I’ve seen from the 25 games I’ve played thus far, however, is an impressive range of experiences. Sophisticated input paradigms that reframe the way games control in such a fun and engaging manner, almost all of which had some form of hidden input sequence that formed the foundation of graduating from play to mastery.

It’s not all roses, however, and while much of my reaction to the game, both positive and negative, has been informed by taste more than some formal analytic criteria, there have been a few hiccups along the way.

UFO 50 has a strange relationship with kayfabe. Ostensibly a collection of hidden gems, it cribs from a lot of real world historical artefacts. Long forgotten titles that largely only exist now as vaporware. Because of this it's hard to decipher whether a particular execution of an idea is the result of maintaining some form of antecedent comprehension, or simply good old fashioned jank.

The issue is that not everything is authentic to the era these games were purportedly built in, and because of this some of the more irksome elements of these games, notably the difficulty of many and rigid handling of some, feel a little contrived, if they were even designed intentionally to be this way.

I’ve also found that quite a number of these titles feel a bit undercooked, like they could easily have sprung out into more substantial, modern and polished games in their own right. Experiences like Waldorf’s Journey, where I could have happily had another three or four worlds to navigate, or more gameplay modes for The Big Bell Race, for example.

The task of making fifty full fat games is no easy feat, of course, and I appreciate that after eight years of development sometimes you just have to get the thing out the door, but when I think about the collective back catalogue of these developers, I can’t help but question whether maybe they should have called this UFO 30 instead and spent a bit more time with those titles that truly slap.

Having said all that, however, I am still excited about these games, and what awaits me in the next 25.

See you next week as we explore more weird and wonderful ludic anachronisms!