Pentiment is more than an RPG

Obsidian's latest offering is a canticle for more interesting choice driven games

I consider myself to be quite an optimistic chap. I like to see the best in every situation but even I will concede that things have been a bit shit recently. Whether we’re talking about a global pandemic, the continued flourishing of a rotten and exploitative economic system, the increasing presence of extreme right wing dog whistles in mainstream media or the fact that Kissinger is still alive, we've been absolutely pelted in recent years.

The result of this is that it's been remarkably difficult to manage the complex array of feelings and feedback that comes from all this. The way we consume art is inexorably intertwined with how we digest the world around us. Good, bad and ugly all form a congealed mass at the centre of our brains. Memory itself but a distant memory, a fractal pattern of half remembered information and fully misremembered emotional intensity.

We live through a culture that has the zoomies. A race through every muddled joy we can muster as a consequence of having to run away from a veritable tsunami of bad news, a rolling ticker of every act and event worldwide. Every hour, minute and second as it happens, resulting in an attention span that leaves no prisoners.

For this reason I can understand why many would see Pentiment as a bit of a snoozefest.

It's slow.

Really slow.

The first piece of drama doesn't occur until many hours in. All you seem to do is eat and drink and draw and discuss Martin Luther. Outside of the expectations of a videogame, that sounds like a great time to me, but it's an experience that is reliant on active interest more so than any roleplaying game I've played.

It's a commitment, for sure, but the glaciality of this opening act, the careful and measured approach to delivering narrative threads, is a huge contributing factor to what I consider the game's greatest success: It creates a world that feels wholly independent of the player, and demands that you live by its rhythm rather than your own, resulting in an experience that unwittingly is a perfect panacea for the busyness of modern culture and a game that is more than just an rpg.

Spoilers to follow

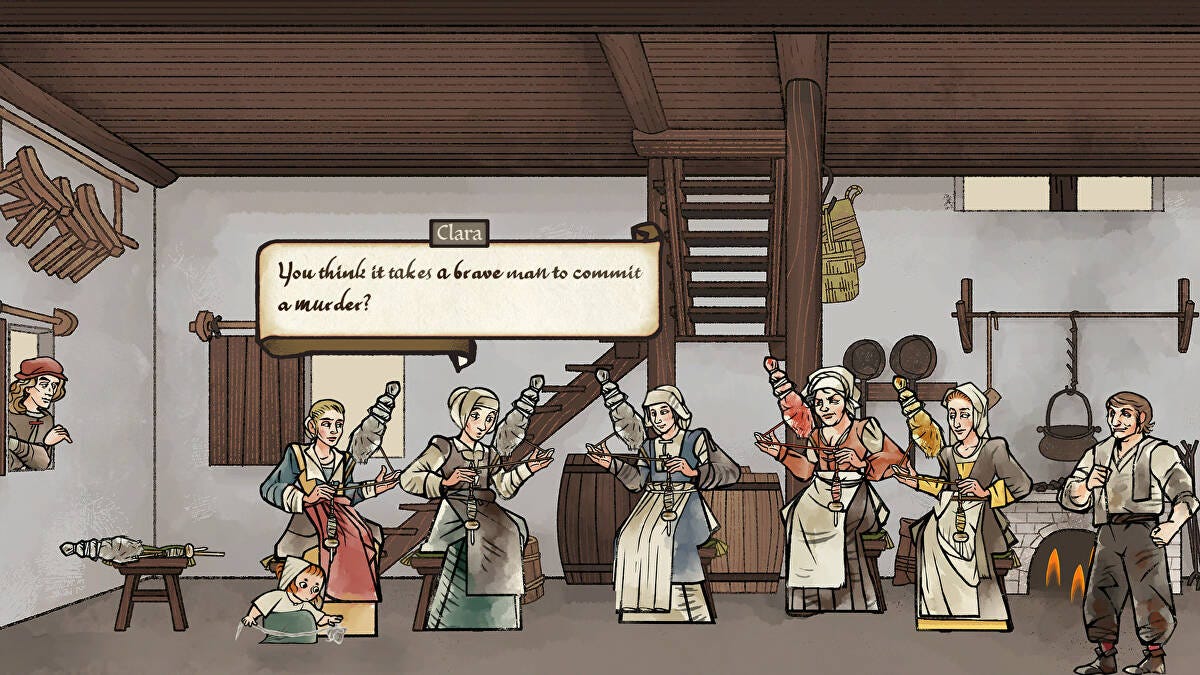

In Pentiment, you play as Andreas Mahler, a young artisan on a rite of passage visiting the town of Tassing in 16th century Bavaria. It's a place that is so very ordinary in its peculiarities, a town where all the big stuff happens somewhere else, some fictional version of the outside world that in reality is fraught with complex political troubles. Tassing, by comparison, feels so terribly small that even the presence of a stranger from another demesne is an event unto itself. Beyond that, all that exists in this sleepy little township is life, death and the meals in-between.

For the first few hours, much of what you do in Tassing is at the beck and whim of this incredibly drawn out sense of living. Time is both agonisingly long winded and frighteningly sparse, the periods of the day zip by as quickly as you can finish your wurst and potage, a single action swings you from sext to nones to vespers to compline and before you know it the day is done and you've maybe achieved a scant couple of things with your time, because you've had no choice but to take your time. Such is the rhythm of life in Tassing.

Many moments after meeting Baron Lorenz Von Rothvogel, an agreeably disagreeable nobleman whose presence has sparked the ire of many a townsperson, he is found murdered in the halls of the Abbey. Discovered with the body, a doddery old priest who is summarily detained as the prime suspect. Andreas, despite being an artist not a lawman, is tasked with investigating the crime, and given very little time to present his findings.

After so much quiet meandering around town this sudden jolt to the system shows the player that time is not something to be trifled with. Choices have to be made, and the care within which consequences have been hidden from you elevates the gravity of this whole situation to hitherto unseen heights. It's not a privilege, it's a burden. The brevity of your window of investigation explained not by some passionate call to justice but the understanding that the murder of a nobleman with friends in high places is not a good look for such a small, unassuming municipality. Someone has to take the fall, whether it's the culprit or not.

Long story short, whatever evidence you unearth you present to the local authority, or choose not to, and inevitably, maybe unfairly, someone pays for this heinous crime.

Then seven years pass.

Andreas's return to Tassing, young protege in tow, is met with a warm welcome. The wistful meandering that the game opened with returns as you reunite with the town folk, now older, perhaps a bit wiser. There's trouble brewing, disagreements with the Abbey over taxation. Conflict among the townspeople over whether decisive action should be taken or not. Some want a quiet life. Others know that it is an option no longer afforded to them.

Eventually, dramatically and somewhat inevitably, someone is killed on the building site of the new rathaus. A very critical someone. A someone for whom any number of neighbours would have reasonable conflict. And once again the hapless artisan Andreas Mahler is tasked with investigating another crime, once again with a frighteningly tight time frame. And once again justice is demanded at the expense of thoroughness.

Events occur, conflict arises, all resulting in the Abbey being burnt to the ground, with Andreas, desperate to save centuries worth of literature, holding ground until he's saved what he can. He does not survive.

Then eighteen years pass.

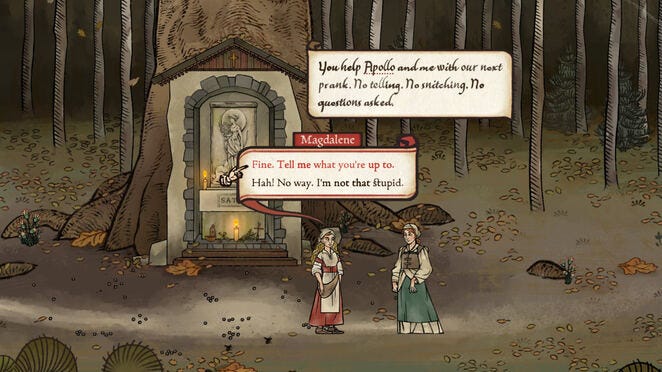

In this final act you take the reins of Magdalene Druckeryn, the daughter of tassing's printmaker, Claus. After her father is assaulted by an unknown stranger in the dead of night, facing the stark reality of mortality, she takes up the mantle of artisan and prepares to work on the Rathaus mural representing the town's history and its legacy.

The slow meandering returns. Magdalene begins her own investigation. Except this one is not specifically at the beck and whim of political pressures or religious strife, although understandably those must be taken into consideration. Magdalene is also afforded what Andreas could never court: Time. Days, weeks, even months pass as Mags deftly draws the truth about Tassing’s history from the townsfolk and makes her decisions about what to add to the mural.

It’s a search for the truth in a more historical sense, one that unveils more than just the events you the player are party to. In the game’s final hours all is revealed, the answer to the mystery that has plagued Tassing not just for two decades, but for centuries, and…well, life goes on.

Pentiment is not an exciting game by any stretch of the imagination but it does have moments of incredibly precise drama that you cannot take your eyes off. A curated selection of moments through time that don’t really feel like events in the way they would in a traditional role playing game, not just things you won't forget but rather things no one will forget.

Pentiment is not really an RPG at all. But it’s hard to say what it actually even is. An adventure game? A murder mystery? A slice of life simulation? There's a very tangible sense that this game is rallying against being boxed into any one particular archetype.

Its creators, Obsidian, are cult favourites, assembled from the remnants of the grandfather's of the genre, responsible for a number of incredibly well regarded, ambitious role playing games and also Alpha Protocol. Heh heh.

When you're the Fallout New Vegas guys, there's a legacy of expectation hanging over your head. It's hard to break away from that, I imagine. Which is all the more impressive that Pentiment looks and feels like…well, not an Obsidian game. In a way, it's a beleaguered response to decades of convention, but there are a few key aspects of the game that I think specifically point to its success as an interactive fable.

Pacing is remarkably important to the story that this game wants to tell you, not in the sense that it hurries you along but rather that it wants to effect the waxing and waning of a small relatively boring community's perception of time. For this they removed stats, levelling up, experience, equipment, skills…well, basically everything bar player movement. The game even controls the speed of text boxes depending on the character you’re speaking to. The old monks take longer to present their dialogue than the youth of the village. It’s something so subtle I only really clocked onto it because Josh Sawyer, the game’s director, mentioned it in an interview.

Choice still drives the game but it’s a very different kind of decision making compared to what we’re used to. You have great agency over who you talk to, how you spend your time, who you take your meals with, as well as key elements of your back story: where you come from, what languages you are proficient in and as such who in this world you can converse with. These choices do affect your experience in the game but I wouldn’t consider this narrative branching in the traditional sense. It’s more focused on how folk remember you as you’re all pulled along the currents of this tale. It has more in common with the Telltale model of storytelling than anything else. People remember the things you say and do, and whether that makes a difference or not…well, let's not spoil everything about the game.

The mechanical domain of Pentiment is designed to move you forward. Nothing holds you up. Regardless of the perceived success or failure of your conversations, the plot always moves on, and sometimes it makes you feel like you never really had any power to change your own fate.

I think a remarkable design decision here is that the very few skill gates that do crop up from time to time are built upon decisions you will have made many moons ago, sometimes even going back hours in game time. And they aren’t obvious things. An off the cuff remark, responding to someone a little too smugly. Sometimes the specialities you choose for yourself at the beginning offer up interesting player specific responses that might not even be really the appropriate choice for the situation. What’s good for the goose isn’t always good for the gander.

Pentiment feels duty bound to be built upon a mountain of regrets, something that filters in nicely to the parts of the story you have no control over. The things that had already happened before you put on your leggings and fancy hat and went galavanting around town. The quiet remorseful moments that Andreas is forced to contend with in the labyrinthine twilight zone between Compline and Matins and the legacy of the unreasonable expectations made upon you the player are one and the same.

And that's the point. A lesson taught in blood, and not your own. This isn’t a playground for your own amusement, a municipal chessboard to preside over and deliberate the most optimal course of action, these are real people. They have their own agendas, their own emotional preferences. Some of them will not like you no matter what you say or do.

Like Martin Bauer. That little shit. Who the hell does he think he is?

Pentiment is a game that feels like a response to a tired formula, a game that understands that after time has passed what people remember of great role playing games is not the systemic intricacies but the moments that made them feel something. The mechanics are there to make the experience. And sometimes what you want is not to feel like you're the king of the world, but rather that you're a part of something bigger than you.