UFO 50 is a game about the history of games. Where it works so well is in how evocative it is about a specific era of that history (albeit with much needed modern bells and whistles have you played some old games recently? Eww!).

Part of that evocation comes down to the design decisions being made that are seemingly at odds with the legacy of it’s creator, and in Planet Zoldath I finally find myself at odds with the game itself.

But I don’t know if my frustrations are born from intention or not.

That’s the fun thing about UFO 50. It’s esoteric nature is very much the point but at the same time it feels cheap to chalk any and all criticism up to the game being designed to ape certain quirks and limitations.

My issues with Planet Zoldath, I’ve discovered after sinking many hours into it, are not born from those intentional limitations but from how irksome the whole experience is. I get the point of the exercise but I don’t feel that cleverness justifies what a pain in the arse it is to actually play.

It’s an audacious design document: An adventure game/scavenger hunt where every aspect is procedurally generated upon start, and where failure means starting the whole thing from scratch.

The execution of these two things is remarkably good. I don’t know what algorithmic wizardry was enacted to ensure that a game that’s all about lock and key navigation puzzles still works when the setup is left to chance, but there was only one run I encountered that was impossible to complete out of lord knows how many.

For the most part it works, all the more impressive due to how constrained it is by the mostly binary functionality of it’s items and obstacles.

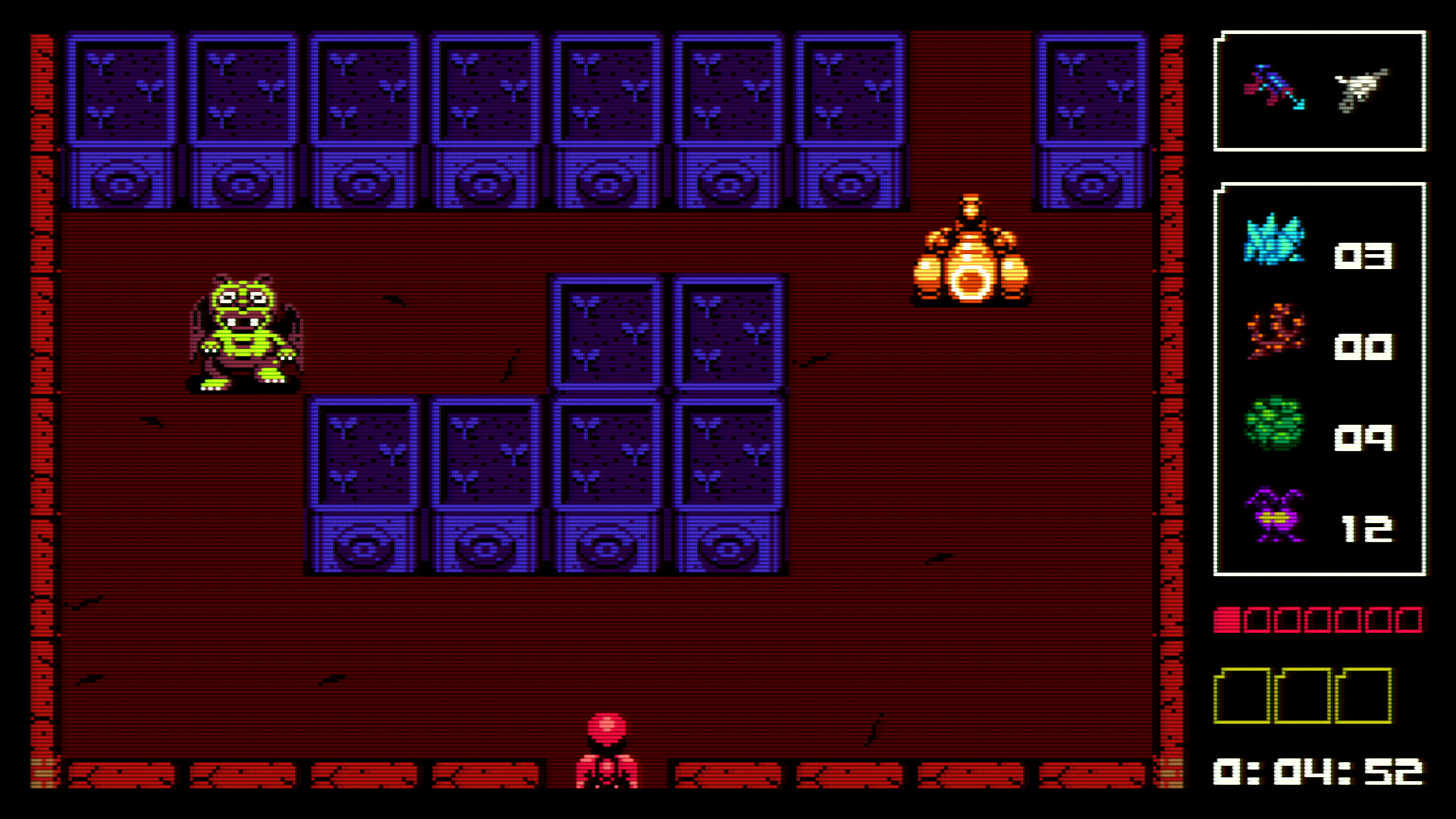

A small hole needs the transmogrifier to pass through. The pink pools of acid need safety boots to navigate without eviscerating yourself. Items on far away ledges need the boomerang to grab. You need a translator to talk to the locals.

It’s quite zelda like in how it presents you with these tools to get the job done but makes you figure out the critical element for success yourself. It’s also not one to shy away from the subtle joy of discovering a hidden rule in an unexpected way. Multiple times during my numerous playthroughs I felt that stem of joy at unfurling yet another constituent part of this ever shifting maze of ideas.

The problem with all this is that there came a time when I had the game fully clocked, and that time came remarkably early on. While each game is unique to the player, the logic that fuels it’s puzzle solving strategies are fixed. There are eight keys to eight locks, in the abstract sense. The components and players might change but the rules stay the same.

It’s that age old dilemma of knowing what to do but struggling to actually do it, and this is because there are many, many dangers on Zoldath, and the galactic traveller you play as has the constitution of a cobweb.

Death comes far too easily for a game that is about puzzle solving not skill mastery. I’m sure anyone who’s played Planet Zoldath will have had the same first experience, stepping out into the great unknown only to be murked in one shot by the first enemy they came across.

As an aside, I really despise it when games do damage on contact, unless your opponent is covered in lava or spikes it always feels cheap. There’s no need for it.

Health pickups give you a slight bulwark against dying, but restoring health is a puzzle unto itself, it’s all too easy to get clipped rounding a hazard just a little too close, and the knowledge that you’ll have to repeat sequences you’ve done dozens of times already results in an experience that can quickly sour.

But what do I know? Maybe that’s the point. Folk didn’t have it all figured out yet in the 80s, and there is a story being told here, if we are willing to listen